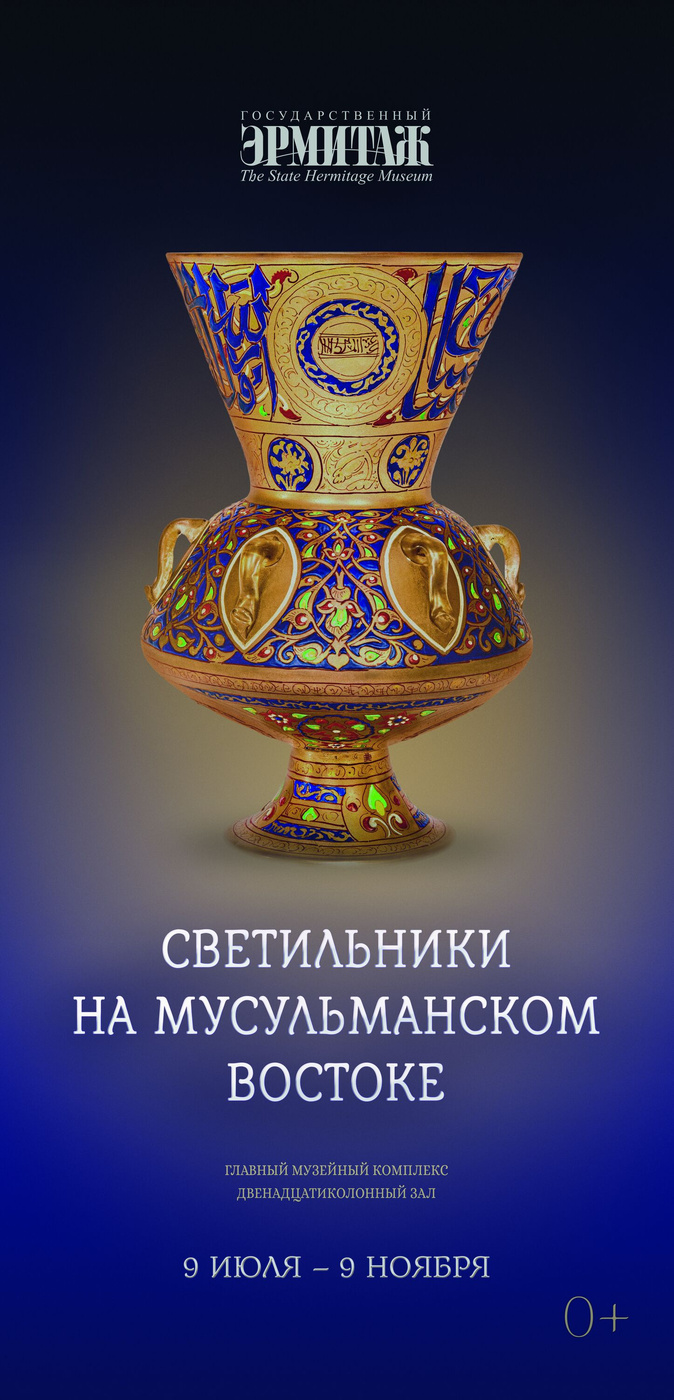

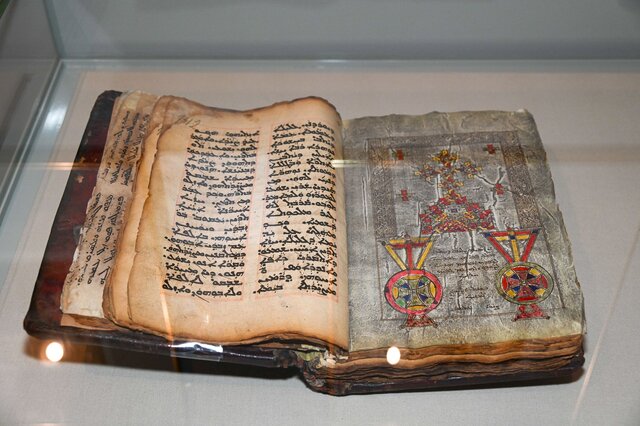

The image of light has been widely used in Islamic art, as it has been employed by artists, poets, and philosophers to describe the divine. As a result, lamps have a significant place in the arts of Muslim countries, as do their depictions in various media. The exhibits showcase the diversity of lamp designs in the Muslim East and their numerous applications throughout the period from the 7th to the 20th centuries. Special attention is given to the historical background and evolution of these forms, as well as the symbolism associated with the depictions of lamps on various materials. Another focus of the exhibition is on the interplay between Muslim and Christian cultures in the Middle East, where similar forms and motifs were used. The exhibition features over 70 pieces, including lamps in a variety of shapes made from metal, ceramic, glass, and their depictions on fabric, hand-painted miniatures, and in stone. Among them are several exhibits created by Christian communities in the Muslim-majority areas. The exhibition is organized into sections based on the types of lamps. This roughly corresponds to the historical timeline of their development and use.

In Muslim places of worship, such as mosques, mausoleums, and madrasas, lighting devices can be used to create different levels of illumination in the architectural space. The uppermost tier of the lighting system was occupied by elaborate chandeliers. These were massive metal structures, to which multiple glass ceiling lamps were affixed. A separate category of lamps included lanterns of various designs, which housed one or more candles. These lamps, dating back to at least the 17th century, were commonly found in Iran and the Ottoman Empire. Following the chandeliers, the next level of lighting in religious buildings served the numerous arcaded areas that comprised a significant portion of the interior space of mosques. This function was fulfilled by vase-shaped lamps that were suspended from the arches in the main prayer hall. The lower tier of lighting for both religious and secular buildings was provided by various floor lighting fixtures. These included metal and ceramic lanterns with a hole for oil filling and a nozzle into which the wick was placed. A large number of these metal lanterns in various shapes have survived, ranging from strictly geometric to zoomorphic designs, and almost all of them have ancient and Byzantine prototypes. The number of lantern wick nozzles could range from one to dozens, and apparently even more. Metal candle holders, typically made from copper alloys such as bronze or brass, have been a common object in almost all Muslim cultures for several centuries. Their shape and size can vary significantly, with the base widening downward, topped by a stem with a candle socket. The shape of thecandle socket often resembles the base, although it is typically smaller. Another type of lighting fixture in the medieval Muslim East was a lamp with a stationary oil reservoir, affixed to the base via a central tube-shaped stem. The wick would be housed within this reservoir; inside many surviving examples, a device for securing the wick is preserved.

Among the most significant exhibits are Mamluk glass lamps with enamel, lamps with reservoirs from the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi, and miniatures from manuscripts of Nizami's "Khamseh" and al-Hariri's "Maqamat".

In Muslim places of worship, such as mosques, mausoleums, and madrasas, lighting devices can be used to create different levels of illumination in the architectural space. The uppermost tier of the lighting system was occupied by elaborate chandeliers. These were massive metal structures, to which multiple glass ceiling lamps were affixed. A separate category of lamps included lanterns of various designs, which housed one or more candles. These lamps, dating back to at least the 17th century, were commonly found in Iran and the Ottoman Empire. Following the chandeliers, the next level of lighting in religious buildings served the numerous arcaded areas that comprised a significant portion of the interior space of mosques. This function was fulfilled by vase-shaped lamps that were suspended from the arches in the main prayer hall. The lower tier of lighting for both religious and secular buildings was provided by various floor lighting fixtures. These included metal and ceramic lanterns with a hole for oil filling and a nozzle into which the wick was placed. A large number of these metal lanterns in various shapes have survived, ranging from strictly geometric to zoomorphic designs, and almost all of them have ancient and Byzantine prototypes. The number of lantern wick nozzles could range from one to dozens, and apparently even more. Metal candle holders, typically made from copper alloys such as bronze or brass, have been a common object in almost all Muslim cultures for several centuries. Their shape and size can vary significantly, with the base widening downward, topped by a stem with a candle socket. The shape of thecandle socket often resembles the base, although it is typically smaller. Another type of lighting fixture in the medieval Muslim East was a lamp with a stationary oil reservoir, affixed to the base via a central tube-shaped stem. The wick would be housed within this reservoir; inside many surviving examples, a device for securing the wick is preserved.

Among the most significant exhibits are Mamluk glass lamps with enamel, lamps with reservoirs from the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi, and miniatures from manuscripts of Nizami's "Khamseh" and al-Hariri's "Maqamat".

Photographs of the exhibition: Alexey Bronnikov.

© The State Hermitage Museum, 2025

A guided tour of the exhibition "Luminaries in the Islamic East", presented by its curator, Anton Pritula, a doctor of philology and leading researcher at the Oriental department.

Organizers and participants

The State Hermitage Museum, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences, The Mardjani Foundation

Mardjani Foundation

Mardjani Foundation